Soil Fertility Dynamics and Xanthomonas Wilt Incidence in Enset (Ensete Ventricosem) Based Farming at Chencha, Southern Ethiopia

Abstract

Enset (Ensete ventricosum) is a vital food security crop cultivated in South and South-western parts of Ethiopia. However, enset production and the farming families have been threatened by Xanthomonas wilt and its spread in the farming system. Thus, this study was conducted to investigate the soil fertility and plant management practices association on the incidence of Enset Xanthomonas wilt. Data on soils fertility and diseases from enset based farming clustered into inner, outer and outfield farm zone were sampled and surveyed. The result indicated that soil chemical properties significantly (p≤0.05) varied from inner to outfield farm zone. Significantly maximum nutrients store revealed in inner enset farm zones. Disease incidence reduced from inner to the outfield enset farm zone. Disease prevalence and disease incidence scored 28.5% and 11.6%, respectively depending on altitude and genotypes. Soil fertility levels in the enset inner and outfield plots were varied purposely to cultivate enset products as kocho, bulla or amicho (cooking type). The variations in soil fertility and Xanthomonas wilt incidence was associated with management practices applied for desired enset products. Therefore, management practices in enset based farming, soil fertility and location of enset planting zones found to be major indicators for disease incidence addressing to device control interventions.

Author Contributions

Copyright © 2025 Zenebe Mekonnen Adare, et al

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Enset (Ensete ventricosum) is a multi-purpose perennial plant mainly cultivated in southern and southwest highlands of Ethiopia for food, feed, medicine, fiber, construction material and many cultural practices 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. The plant belongs to order Scitamineae, family Musaceae and genus Ensete 7. It is a staple food security crop recognized for its higher productivity, environmental sustainability and adaptability than most cultivated cereal crops in Ethiopia 8, 9. Enset supports more than 20 million people in Ethiopia 10. Enset based farming is a sustainable traditional agricultural system predominantly as home gardens and the outfields are used for annual crops. It is one of the most reliable and strategic crop resisting transient droughts, heavy rain and flooding that would typically destroy other crops especially during adverse climatic conditions 11. The crop is grown and distributed at altitudes between 1500 and 3100 m.a.s.l, but best suited between 2000 and 2750 m.a.s.l., with an average annual rainfall of 1100 to 1500 mm (Brandt et al., 1997). It grows well in areas with fertile soils, temperatures between 16 and 20°C, relative humidity 63% and 80%, pH range between 5.6 and 7.3.

Enset based farming is solely reliant on nutrient supply from animal manure and household waste without application of inorganic fertilizer. Soils of enset near to home gardens were more fertile when compared to other farm enterprises due to frequent provision of manures and household 12, 13, 14. Hence, there exists a change in soil nutrient content. Gradients in soil fertility within the enset home garden as a result of difference in management practices with distance from the house were reported by Sabura et al. (2021).

A reconnaissance survey at highlands of Chencha, Gamo zone showed that farmers dominantly practice enset cultivation in home gardens but annual crops surround the enset home gardens or outfields 14. The home garden were perceived cultivating enset landraces mainly for processing types while the outfield, which is found at a distance from the home garden, is presumed as being planted with cooking type enset landraces locally called ‘Cheero’ (14. Planting location (distance from homestead) also differ depending on enset product preferred for food type and soil fertility of the garden 14. As Shara et al. (2021) report, soil fertility status of a garden was related with farmer’ management practices applied for a preferred enset product within the enset home garden and altitude which in turn linked to Xanthomonas wilt (EXW) incidence. Studies in banana, family of enset, show that fine tuning disease management strategies on-farm has helped to reduce EXW 15, 16. This indicates that exploring farm management practices in enset still remains very important strategy to reduce disease spread. It also prevent new infections, as an immediate disease control option, suggesting need for thorough understanding of the status of farm management tactics in enset systems and the association with disease incidence at various distances from the house.

Furthermore, experimental evidence showed that deficiencies in certain nutrients such as phosphorus hasten susceptibility to EXW in Gamo highlands 17. However, information on disease incidence over the farming zones within an enset farm linked with farm management per enset product type is not available. Although the disease has been observed in entire enset belt, the extent of disease incidence and spread varies from region to region at landscape level. The variation observed was linked with environment that favors disease development or plant susceptibility, mainly altitude driven moisture and temperature as well as management practices such as soil fertility 18, 19, 14. The knowledge of such management practices and the link to disease spread may help to develop management measures for EXW. Therefore, studying crop management practices related to growing enset for processing type (kocho and bulla) and direct cooking (amicho), quantifying soil fertility, characterizing landraces in inner, outer and outfield or ‘Cheero’ zones (plots) and the association with xanthomonas wilt incidence may help to understand the EXW pathogen niche in a complex traditional enset farming systems and to devise context specific options for disease management.

Materials and Methods

Study area description

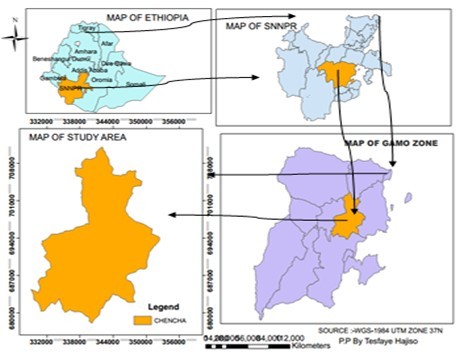

The study was carried out at Chencha, South Ethiopia Regional State, geographically located at 370 29' 57'' to 370 39' 36'' E longitude and 60 8' 55'' to 60 25' 30'' N latitude during March 2022 to February 2023 (Figure 1). The area is attributed with quite marked topographic variation (rolling mountains, steep slops, flat to undulating plateaus 20, 14 and soil types of reddish, deeply weathered Nitisols and Luvisols 21.

Sampling design and treatments

Enset farm established in farmers’ field within 2500 to 3000 altitudinal range of the study area was purposively selected consisting four randomly selected villages namely Doko yoyira, Tsida, Lakana maldo and Dorze holo. Three housholds were randomly selected in each village. Each household enset farm clustered into three farm zones (inner (IR), outer (OR) and outfield (OF) i.e. cheero plots).

The altitudinal range used for the study was selected due to dominance of enset based farming system and uniformity of households over the range for sampling. The inner home garden (IR) is enset farm within 4 to 6 m of homestead that receives more solid and liquid manure, organic waste, ashes and house residues, the outer home garden (OR) is enset farm that receive less amount of manure, organic wastes and house residues and the outfield or locally called cheero is enset farm which receives organic manure only at transplanting time and used for enset plant cultivated only amicho production.

The total list of 1450 households was collected from the agricultural extension office. Accordingly, a sample size of 35, 48, 31, 65 households from the respective villages were selected with the procedure suggested by Yemane (1967). The selected households were used for interview with open structured questionnaire and focus group discussion.

Where,

N= is the population size e= is the level of precision (5% to 10%)

n= is sample size K= is the interval the sample would be taken

Data collection

Soil physical and chemical analysis

Soils of the upper 25cm depth in which most of the plant roots typically distributed (Zewdie et al., 2008),14 was sampled in each farm zone from five spots by using auger and a composite sample per farm zone used for analysis. One composite soils for each farm zone (IR, OR and OF) were collected replicated in three household farm per village/kebele. The total of 36 composite soil sample size were air dried at room temperature, grounded and sieved with 2 mm size and used to analyze pH, EC, soil texture, available phosphorus, OC and OM at the Arba Minch University botany and environmental science laboratory. The measures of OM and available phosphorus were used as indicators for soil quality and to compare the amount of soil nutrients at enset garden and to infer the relationship between inner, outer and outfield home garden.

The OM content was extracted by the dichromate oxidation method (Walkey and Black, 1934). Available phosphorus was estimated by Olsen´s procedure 22. The soil EC and pH was measured using disinfected digital EC and pH meter, respectively. Soil texture was determined by the hydrometer method 23.

Farm management practices and Enset Xanthomonas wilt

Farm management practices such as manure application, cultivation, leaf pruning, enset landraces and reaction to EXW and Enset Xanthomonas wilt (EXW) incidence at inner, outer and outfield enset farm plots were interviewed on sampled households with semi-structured questionnaire. The characteristic visual symptoms such as yellowing and wilting of leaf, yellowish or creamy bacterial ooze at cut leaf petiole/ edge of pseudostem for claimed disease presence were visually observed, Bacterial ooze collected from petiole or pseudostem of suspected plant was cultured in a semis elective media for further confirmation (Thwaites et al., 2000) 24.

Focus group discussion

Association of farm management practices with enset production type, soil fertility gradient, xanthomonas wilt disease incidence, transmission and indigenous practices of control was carried out with groups of participants comprised of four elder groups, four women, four development agents, two expert, four village leaders and four model farmers. Semi structured questions and open ended subjects were used to initiate free discussion among the focus group participants and to minimize subjective responses.

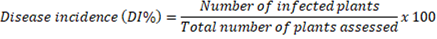

Disease incidence (DI%): Disease incidence was calculated by counting the number of infected enset plants assessed in each farm zones and dividing to the total number of enset plants in each garden plot of the sampled households (HHs) 25.

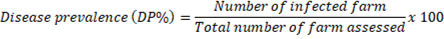

Disease prevalence (DP %): Disease prevalence was determined as the presence and absence of EXW in enset fields assessed, and calculated using the formula:

Data analysis

Data for normality were tested with normal probability plot (P-P and Q-Q) and histogram. The soil physical and chemical properties indicating the gradient in soil fertility between IR, OR and OF was determined with a one-way ANOVA analysis data with SAS version 9.0. The mean difference between the soil fertility records was tested with least significant difference (LSD) at 5% probability level. For every sample analysis, the mean and standard deviation was computed for the three replications of each sample. The strength and weakness of purpose of enset production with enset management practices, soil fertility levels and enset xanthomonas wilt disease incidences was tested with simple correlation analysis. Data collected during interview and focus group discussion analyzed using SPSS version 20.

Results and discussion

Enset management practices across farming zones

Indigenous management practices varied across enset farm zones, with the intensity of management decreasing from the homestead towards the outfield (Table 1). Household surveys and group discussions revealed a consistent trend: the frequency of hoeing, weeding, leaf pruning, and manure application diminished from the inner farm zone outwards. Specifically, hoeing/weeding and leaf pruning were performed twice per year in the inner farm zone by 83.24% of respondents, compared to 76.54% in the outer zone (Table 1). Notably, 97.21% of respondents reported hoeing their outfield enset plots and pruning leaves only at the time of transplanting. This suggests that enset home gardens (homestead and closer gardens) receive more intensive management and care. This finding aligns with Tsegaye and Struik (2002), who reported that enset home gardens are weeded periodically, 2-3 times a season, and Kebede et al. (2021), who noted weeding frequencies ranging from once every 1–5 years depending on elevation.

Table 1. Hoeing/weeding and leaf pruning frequency per enset farm zone per year| Hoeing/Weeding and Leaf Pruning by Farm Zone | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farm zone | 3× | 2× | 1× | |||

| Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | |

| IR | 23 | 12.85 | 149 | 83.24 | 7 | 3.91 |

| OR | 9 | 5.03 | 137 | 76.54 | 33 | 18.44 |

| OF | 5 | 2.79 | 174 | 97.21 | ||

Regarding manure application, 91.06% and 74.86% of respondents reported frequent annual application in the inner and outer farm zones, respectively. In contrast, nearly all respondents (almost 100%) applied manure in the outfield only at the time of transplanting (Table 2). This perceived fertility gradient across enset farm zones, acknowledged by 82.7% of respondents (Table 3), suggests the impact of varying soil management practices by farming families. The frequent application of manure and household waste management around the homestead likely contribute significantly to the soil fertility gradient observed in enset home gardens 14. This aligns with Tsegaye and Struik (2002), who also reported that the rate, timing, and method of manure application result in soil fertility differences between home gardens and the wider enset farm.

Table 2. Manure application frequency per enset farm zone per year.| Manure application frequency per year | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequently | 3x | 2x | 1x | |||||

| Farm zone | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent |

| IR | 163 | 91.06 | 9 | 5.03 | 7 | 3.91 | 0 | 0 |

| OR | 134 | 74.86 | 39 | 21.79 | 6 | 3.35 | 0 | 0 |

| OF | 179 | 100 | ||||||

| Management questions | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil fertility gradient in inner, outer and cheero plots | Yes | 148 | 82.7 |

| No | 31 | 17.3 | |

| Enset plants and leaves most frequently harvested for home use from farm zone | IR | 169 | 94.4 |

| OR | 10 | 5.6 | |

| OF | 0 | 0 | |

| Enset plants and leaves not harvested for home use from farm zone | IR | 12 | 6.7 |

| OR | 18 | 10.05 | |

| OF | 149 | 83.2 |

Enset landrace and enset product type alignment with planting farm zone

Interviews and field observations revealed that enset landraces selected for kocho production exhibited vigorous growth and high yields when cultivated in the inner farm zones. As shown in Table 4, 69.3% of informants employed specific enset landraces and clustered planting arrangements based on the intended food product. Respondents consistently identified kocho, bulla, and amicho as the primary enset food products. Particularly, 60.03% reported cultivating varieties for kocho and bulla in both inner and outer farm zones, while 87.15% grew enset for amicho production further away from home gardens (OF) (Table 4). This suggests that enset plants grown for kocho production benefit from close supervision, fertile soil, and frequent management. Supporting this, Sabura et al. (2021) observed that manure, organic wastes, ashes, and household refuse were frequently applied in enset farm zones closer to the homestead but not in the outfield zones.

Table 4. Enset landraces per enset food/product types allocation per farm zone| Management questions | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major food products from enset | Kocho | 179 | 100 |

| Bulla | 179 | 100 | |

| Amicho | 179 | 100 | |

| Enset planting clustered spatially per enset food type | Yes | 124 | 69.3 |

| No | 55 | 30.7 | |

| Planting zone of Enset landraces for kocho production | IR | 49 | 27.4 |

| OR | 22 | 12.3 | |

| OF | 0 | ||

| Both IR and OR | 108 | 60.3 | |

| Enset food type preferred planting at cheero plots (outfield zones) | Kocho | ||

| Amicho | 156 | 87.15 | |

| Both | 23 | 12.85 |

Soil fertility gradient over enset farm zone related to enset product types

Analysis of soil particle size distribution in the IR, OR, and OF (cheero plot) farm zones revealed no significant differences. The soil texture across all farm zones was classified as clay loam (Table 5). The consistent percentage of silt content suggests that the dominant mineral particle in the enset farm zone is relatively uniform. However, despite the uniform particle size distribution, the results also indicated that soil management practices and the type of enset cultivars grown across the farm zones do have a significant influence on particle size distribution. Similarly, the consistent percentage of silt content in enset farm zones was also documented by Kebede et al. (2021).

Table 5. The effects of farm zones on soil texture in chencha districts| Farm zones | Sand (%) | Silt (%) | Clay (%) | Textural class |

| IR | 39.27 | 32 | 28.73 | Clay loam |

| OR | 36.27 | 32 | 31.73 | Clay loam |

| OF | 29.27 | 32 | 38.73 | Clay loam |

| LSD (0.05) | 16.24 | 7.89 | 12.25 | |

| p-value | 0.4249 | 1 | 0.2355 |

Analysis of soil chemical properties revealed significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) among the farming zones, with mean values generally decreasing from the inner/home garden (IR) to the outfield (OF) zones (Table 6). Specifically, the IR farm zone exhibited significantly higher values for available phosphorus (28.52 mg/kg), electrical conductivity (EC) (2.11 dS/m), pH (6.63), organic matter (OM) (3.66%), and organic carbon (OC) (2.12%) compared to the OF zone, which recorded minimum values of 3.29 mg/kg for available phosphorus, 0.69 dS/m for EC, 5.78 for pH, 2.69% for OM, and 1.56% for OC. The higher phosphorus availability in the IR zone is likely related to its optimal pH range for phosphorus solubility, while the lower availability in the OF zone may be attributed to aluminum fixation at its lower pH values. The significantly lower pH observed in the outfield enset farm zone (5.78) compared to the inner farm zone (home garden) (6.63) and outer home garden (6.08) aligns with findings by Sabura et al. (2021) regarding soil fertility status and nutrient distribution between the inner and outfield farm zones.

Table 6. Soil chemical properties (means ± SD) across enset farm zones.| Farm zone | OC (%) | OM (%) | pH | EC (dS/m) | Pav (mgkg-1) |

| IR | 2.12±0.18a | 3.66±0.32a | 6.63±0.44a | 2.11±0.52a | 28.52±6.5a |

| OR | 1.89±0.27b | 3.46±0.50a | 6.08±0.41b | 1.06±0.38b | 12.32±6.39b |

| OF | 1.56±0.20c | 2.69±0.34b | 5.78±0.37b | 0.69±0.23c | 3.29±1.58c |

| Mean | 1.86±0.32 | 3.27±0.57 | 6.16±0.54 | 1.29±0.72 | 14.71±11.78 |

| LSD (0.05) | 0.18 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 4.43 |

| CV% | 11.96 | 12.1 | 6.73 | 30.44 | 36.29 |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

These results highlight the impact of household waste and frequent manure application practices by the farming community, consistent with farmer responses during the survey. Enset plants in the OF zone typically receive manure only at the time of transplanting (sucker stage). The observed gradient in soil fertility levels across farm zones likely arises from variations in farmers' management practices, which are also linked to preferred enset products. Field surveys indicated that landraces for kocho production are primarily cultivated in the IR farm zone, while those for amicho production are grown in the outfield zone. This finding is supported by Sabura et al. (2021), who reported significantly higher soil chemical properties in the inner zone compared to the outer zone, with the exception of available aluminum.

Association of EXW incidence, enset food product type based management and soil fertility gradient

Prevalence and incidence of EXW disease in enset farm zones

Of the 179 enset gardens surveyed (including the 12 households or 36 farm zones where soil properties were analyzed), 51 farms (28.49%) exhibited disease symptoms, while 128 gardens (71.51%) showed no symptoms (Table 7). The observed variation in disease prevalence across kebeles/villages could be due to differences in enset landrace tolerance or susceptibility to EXW, or variations in altitude influencing disease incidence. Furthermore, disease incidence is linked to cropping history, particularly if the land previously hosted infected plants or if susceptible landraces were used for planting. Overall, the results indicated a low distribution of the disease across the enset production zones, with higher severity observed in regions with a history of the disease. Similar results were presented by Muzemil et al. (2021) who reported considerable variation between enset land races towards xanthomonas wilt.

Table 7. Prevalence and incidence of EXW disease in the study area.| Sample kebeles | Number of assessed farms | Number of symptomatic farms | Disease Prevalence (%) | Disease Incidence (%) |

| Lakana maldo Dorze holo | 31 | 9 | 29.03 | 11.6 |

| 65 | 14 | 21.54 | 12.7 | |

| Tsida Doko yoyira | 35 | 13 | 37.14 | 11.4 |

| 48 | 15 | 31.25 | 10.6 | |

| Total Mean | 179 | 51 | 118.96 | 46.3 |

| 12.75 | 29.74 | 11.6 |

EXW disease incidence and farm management practices

The result indicated that disease incidence was observed in both inner and outer zones of the enset farms, with a consistent decrease from the inner to the outer zones across all surveyed kebeles. (Table 8). No incidence of EXW disease was observed in the outer areas of the enset farms across all sampled study sites. This suggests a potential link between the disease and factors associated with the inner farm zones, such as the intensity of farm management practices and soil fertility gradients. The higher incidence of the disease in inner farm zones, where frequent hoeing and leaf pruning are common alongside higher soil fertility and plots dedicated to enset processing, further supports this association. The result showed the association of disease incidence for soil attributes results presented in Table 6 where significant high score for OC, pH, EC and Pav content observed from inner to outfield farm zones. Reduced probability of disease spread on cooking type enset landraces planted in the outfields with less frequency of hoeing and leaf pruning also indicated importance of farm tools in spreading disease. In addition, outfield farm zones practiced with less manure application indicating the reduced incidence of EXW relation with low fertility status of the soil. The present findings are consistent with the work of Tsegaye and Struik (2000), which indicated that a single transplant and reduced field practices of enset suckers, accelerates maturity, ensures a reasonable yield, and diminishes susceptibility to diseases and pests. The findings indicate a correlation between increased plant contact during field operations and a higher incidence of disease.

Table 8. Incidence of EXW disease (DI %) across enset farm zones (N= 179)| Farm zones | Total number of enset plants counted | Total number of symptomatic plants | DI% |

| IR | 560 | 119 | 21.5 |

| OR | 725 | 97 | 13.4 |

| OF | 809 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean | 11.6 |

Growth stage and incidence of EXW disease

Field observations, group discussions, interview data, and farmers' experiences consistently showed that enset plants are susceptible to EXW infection at all growth stages. However, the results indicated a higher susceptibility to Xanthomonas wilt disease during the middle growth stage (77.7%), compared to the younger (11.7%) and productive stages (10.6%) (Table 9). This suggests an inverse relationship between enset plant maturity and susceptibility to the disease, with susceptibility decreasing as the plant ages. This finding contrasts with Gizachew et al. (2008), who reported higher susceptibility in younger enset plants to infection via contaminated tools. In the IR farm zone, frequent harvesting and leaf pruning for home use likely contribute to disease transmission through farm tools. Furthermore, consistent with the soil fertility gradient across farm zones, the study also revealed that 88.3% of respondents observed differences in the time it takes for enset plants to reach maturity for food production across these zones (Table 9).

Table 9. Age of enset and EXW disease susceptibility at IR, OR and OF farm zones| Management questions | Category | Frequency | Percent |

| Age difference in enset plants to reach for food at IR, OR and OF farm zone | Yes | 158 | 88.3 |

| No | 21 | 11.7 | |

| Stage the enset plants susceptible to enset xanthomonas wilt disease | younger stage (1-2) year | 21 | 11.7 |

| middle stage (2-4) year | 139 | 77.7 | |

| productive stage (≥ 4 years) | 19 | 10.6 |

Incidence of EXW disease and soil fertility

Analysis of variance revealed significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) in available phosphorus (Pav) across farm zones. Specifically, the IR farm zone exhibited the highest Pav levels, while the OF farm zone showed the minimum, in both symptomatic and non-symptomatic plots (Table 10). Similarly, significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) were observed for pH and electrical conductivity (EC), with the IR farm zones recording higher values in both symptomatic and non-symptomatic gardens. In contrast, the analysis showed no significant difference in organic carbon (OC) and organic matter (OM) between the IR and OR farm zones for both symptomatic and non-symptomatic gardens. Notably, the soil chemical properties did not differ significantly between symptomatic and non-symptomatic farm zones in this study. However, Sabura et al. (2021) reported higher levels of Pav and available calcium (Caav) in symptomatic gardens compared to non-symptomatic ones. Although specific recommendations for enset are lacking, existing literature suggests a link between variations in soil fertility management and plant susceptibility to Xanthomonas wilt disease in enset 14, 19, 26 and banana 27

Table 10. Properties of soil (mean ± SD) among symptomatic and non-symptomatic enset farm zones (N=36).| Soil properties of symptomatic | Farm zone | pH | EC (dS/m) | OC (%) | OM (%) | Pav (mg/kg) |

| IR | 6.61±0.61a | 2.06±0.54a | 2.10±0.17a | 3.62±0.30a | 23.09±4.74a | |

| OR | 6.06±0.41ab | 1.05±0.44b | 1.81±0.31a | 3.35±0.60a | 15.40±7.75b | |

| OF | 5.62±0.46b | 0.72±0.23b | 1.47±0.23b | 2.55±0.40b | 3.11±1.66c | |

| Garden (n= 18) | LSD (0.05) | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.30 | 0.55 | 6.56 |

| CV% | 8.21 | 33.43 | 13.71 | 14.20 | 38.45 | |

| Soil properties of non-symptomatic garden (n= 18) | IR | 6.66±0.26a | 2.16±0.53a | 2.14±0.21a | 3.69±0.36a | 27.12±4.47a |

| OR | 6.11±0.45b | 1.07±0.34b | 1.98±0.22a | 3.58±0.41a | 9.24±2.63b | |

| OF | 5.93±m0.24b | 0.67±0.28b | 1.65±0.14b | 2.84±0.23b | 3.48±1.64c | |

| LSD (0.05) | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.41 | 3.86 | |

| CV% | 5.28 | 30.16 | 9.9 | 9.98 | 23.66 |

Enset landraces and their reaction to Xanthomonas wilt disease

Enset landraces under cultivation of the study area and their reaction for EXW disease was interviewed with local farmers. The study recorded about 27 types of enset landraces and the interaction with EXW disease as local farming community report (Table 11). The result showed only two enset landraces (Masa maze and Maze) show less susceptibility to EXW disease while 25 landraces reported susceptible to the disease. The findings of Abera (2017) from the south-western Ethiopia region, also showed that over 82.5% of enset landraces were susceptible to EXW and enset landraces, ‘Mazziya and Shododinya’, were relatively better tolerance to EXW disease. Similarly, Fikre & Gizachew (2007) reported that enset variety, Mazia, was tolerant to EXW.

Table 11. Enset landraces, identity and reaction to EXW disease| No | Enset landraces | Uses | Tolerant | Susceptible | Midrib color | pseudostem color | ||

| Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | |||||

| 1 | Alanga | Kocho | 94 | 52.5 | 85 | 47.5 | Grey | Green |

| 2 | Beshera | Kocho and amicho | 42 | 23.46 | 137 | 76.54 | Black | Black |

| 3 | Bodha | Kocho and amicho | 38 | 21.23 | 141 | 78.77 | Brown | Brown |

| 4 | Booza | Kocho | 33 | 18.43 | 146 | 81.56 | Red | Red |

| 5 | Cacao | Amicho | 21 | 11.7 | 158 | 88.3 | Black | Black |

| 6 | Camise | Kocho and amicho | 17 | 9.5 | 162 | 90.5 | Black brown | Black brown |

| 7 | Charga | Kocho | 83 | 46.4 | 96 | 53.6 | Red | Green |

| 8 | Chamo | Kocho | 70 | 39.1 | 109 | 60.9 | Red | Green |

| 9 | Cooce | Amicho | 24 | 13.4 | 155 | 86.6 | Black brown | Black |

| 10 | Dokoze | Kocho and amicho | 66 | 36.9 | 113 | 63.1 | Grey | Green |

| 11 | Falake | Kocho | 53 | 29.6 | 126 | 70.4 | White | White |

| 12 | Gadha zinke | Amicho | 51 | 28.5 | 128 | 71.5 | Deep red | Black |

| 13 | Gena | Kocho | 58 | 32.48 | 121 | 67.6 | Red brown | Red brown |

| 14 | Geze zinke | Amicho | 88 | 49.2 | 91 | 50.8 | Black | Black |

| 15 | Kalsa | Kocho | 75 | 41.9 | 104 | 58.1 | Black | Brown |

| 16 | Katise | Kocho | 113 | 63.1 | 66 | 36.9 | Green | Grey |

| 17 | Katane | Kocho | 43 | 24 | 136 | 76 | Brown | Black |

| 18 | Kunka | Amicho | 39 | 21.8 | 140 | 78.2 | Red | Black red |

| 19 | Lofe | Amicho and medicinal | 26 | 14.5 | 153 | 85.5 | Light red | Light red |

| 20 | Masa maze | Kocho | 179 | 100 | 0 | 0 | Black | Black |

| 21 | Maze | Kocho | 179 | 100 | 0 | 0 | Brown | Black |

| 22 | Orgozo | Kocho and amicho | 21 | 11.7 | 158 | 88.3 | White | White |

| 23 | Phello | Amicho | 33 | 18.4 | 146 | 81.6 | Brown | Black |

| 24 | Sorghe | Kocho | 126 | 70.4 | 53 | 29.6 | Brown | Grey |

| 25 | Suyite | Amicho and medicinal | 71 | 39.7 | 108 | 60.3 | Wine | Wine |

| 26 | Wossa' ayfe | Kocho | 68 | 38 | 111 | 62 | White | White |

| 27 | Zinke | Amicho | 41 | 22.9 | 138 | 77.1 | Deep red | Brown |

The disease incidence also associated with planting zone of enset around homestead. According to the survey data, 93.3% of informants showed disease devastation at the inner farm zone and 88.3% responded the disease incidence at both inner and outer farm zones (Table 12) suggesting the association of disease with farm management and fertility of the garden (Table 6 and Table 8). Landraces of enset used for processed products (kocho and Bulla) were recommended planting at around homestead and amicho was used to plant at OF farm zone.

Table 12. EXW disease symptoms and farm zones observed and level of infestation| Management questions | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease symptoms observed in enset farm zones | Yellowing of leaf | 179 | 100 |

| Wilting of leaf | 179 | 100 | |

| Bacterial ooze yellowish excretion | 179 | 100 | |

| Farm zones observed for EXW disease symptoms | All farm zones | 21 | 11.7 |

| IR and OR farm zones | 158 | 88.3 | |

| Outfield | 0 | 0 | |

| Enset farm zone high in EXW disease devastation | IR | 167 | 93.3 |

| OR | 0 | 0 | |

| IR and OR | 12 | 6.7 | |

| OF | 0 | 0 |

The finding was similar with Sabura et al. (2021), who reported that enset varieties grown for the fermented product of the pseudostem were transplanted to the fertile inner zone and varieties for eating the cooked corm remain in the outer, less fertile zone and receive manure only during their earlier growth stages.

Conclusion

The study results revealed a soil fertility gradient across enset farming zones, decreasing towards the outfield, and variations in farm management practices (manure application, hoeing frequency, weed management, and leaf pruning) based on the preferred enset food type. Processed enset food products (Kocho, Bulla) were typically cultivated around the homestead and in plots receiving frequent management to maintain soil fertility. In contrast, the cooking type (Amicho), which does not require fertile soil or intensive management, was predominantly grown in outfield farm zones. The spatial arrangement of enset cultivars was also linked to the desired food product quality, with landraces for Kocho and Bulla being allocated to fertile plots to enhance pseudostem and corm production. Notably, the study showed a higher disease incidence in the IR farm zone compared to the OF farm zone, suggesting an association between disease, soil fertility gradients, and management practices. Furthermore, very few enset landraces exhibited complete resistance to EXW disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support given by Arba Minch University to codnduct the study.

The Declaration of Interests

I have nothing to declare.

Data statement

Portion of the research data is attached with the manuscript. The survey data is available in the manuscript, Table 11.

References

- 1.Kebede W, Birhanu B, Vegard M, Jan M. (2021) Soil organic carbon and associated soil properties in Enset (Ensete ventricosum Welw. Cheesman)-based home gardens in Ethiopia. , Soil & Tillage Research 205, 1-11.

- 2.Abreham S, Gecho Y, Tora M. (2012) Diversity, challenges and potentials of enset production, Food science and quality management. 7, 24-31.

- 3.Tesfaye B, Lüdders P. (2003) Diversity and distribution patterns of enset landraces in Sidama, Southern Ethiopia, Genetic Resource. , Crop Evol 50, 359-371.

- 4.Nurfeta A, Tolera A, L O Eik, Sundstøl F. (2008) Yield and mineral content of ten enset (Ensete ventricosum) varieties. , Trop. Anim. Health Prod 40, 299-309.

- 5.Y Kebebew Tsehaye, F. (2006) Diversity and cultural use of enset (Ensete ventricosum (Welw.) Cheesman) in Bonga in situ conservation site, Ethiopia, Ethno botany research and applications. 4, 147-157.

- 6.Yemataw Z, Mekonen A, Chala A, Tesfaye K, Mekonen K et al. (2017) Farmers’ knowledge and perception of enset xanthomonas wilt in southern Ethiopia, Agric. Food secure. 6, 1-12.

- 7.S A Brandt, Spring A, Hiebsch C, J T McCabe, Tabogie E et al. (1997) The tree against hunger. Enset-based agricultural systems in Ethiopia, Washington DC: American association for the advancement of science. 56.

- 8.Tsegaye A, P C Struik. (2001) Enset (Ensete ventricosum (Welw.) Cheesman) kocho yield under different crop establishment methods as compared to yields of other carbohydrate-rich food crops. , NJAS-Wagen. J. of life sci 49(1), 81-94.

- 9.Hunduma T, Sadessa K, Hilu E, Oli M. (2015) Evaluation of enset clones resistance against enset bacterial wilt disease (Xanthomonas campestris pv. , musacearum), J. Veterinary Sci. Technolo 6.

- 10.J S Borrell, M K Biswas, Goodwin M, Blomme G, Schwarzacher T et al. (2019) Enset in Ethiopia: A poorly characterized but resilient starch staple. , Ann. Bot 123, 747-766.

- 11.Awol Z, Zerihun Y, Woldeyesus S, Sadik M, Daniel A. (2014) On farm cultivar diversity of enset (Ensete ventricosum (Welw.). in Southern Ethiopia, Institute of Development Studies 4(1), 63-83.

- 12.Amede T, Taboge E. (2007) Optimizing soil fertility gradients in the enset (Enset ventricosum) systems of the Ethiopian highlands. Trade-offs and local innovations. In advances in integrated soil fertility management in Sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and opportunities. 289-297.

- 13.Zelleke G, Getachew A, Abera D, Rashid S. (2010) Fertilizer and soil fertility potential in Ethiopia: Constraints and opportunities for enhancing the system, IFPRI. , Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 63.

- 14.Sabura S, Swennen R, Deckers J, Weldesenbet F, Vercammen L et al. (2021) Altitude and management affect soil fertility, leaf nutrient status and xanthomonas wilt prevalence in enset gardens. , Soil 7, 1-14.

- 15.Blomme G, Kim J, Walter O, Fen B, Jules N et al. (2014) Fine tuning banana xanthomonas wilt control options over the past decade in east and central Africa. , European J of Plant Path 139(2), 1-17.

- 16.Blomme G, Dita M, K S Jacobsen. (2017) Bacterial diseases of bananas and enset. Current state of knowledge and integrated approaches toward sustainable management, Frontiers in plant science. 8, 1290.

- 17.Sabura S. KU Leuven (2022) Environment and management influence early performance and xanthomonas wilt in enset (Ensete ventricosum) in Gamo Highlands, Southern Ethiopia. PhD thesis , Belgium

- 18.Zerfu A, S L Gebre, Berecha G, Getahun K. (2018) Assessment of spatial distribution of enset plant diversity and enset bacteria wilt using geostatistical techniques in Yem special district. , Southern Ethiopia, Environ. Syst. Res 7, 1-13.

- 19.Haile B, Fininsa C, Terefe H, Hussen S, Chala A. (2020) Spatial distribution of Enset bacterial wilt (Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum) and its association with biophysical factors in southwestern Ethiopia. , Ethiop. J. Agric. Sci 30(3), 33-55.

- 20.T, Molen M K Van Der, P C Struik, Combe M, P A Jiménez et al. (2018) The combined effect of altitude and meteorology on potato crop dynamics: A 10-year study in the Gamo Highlands. , Ethiopia, Agric. For. Meteorol 262, 166-177.

- 21.Coltorti M, Pieruccini P, K J Arthur, Arthur J, Curtis M. (2019) Geomorphology, soils and palaeosols of the Chencha area (Gamo Gofa, south western Ethiopian Highlands. , J. of Afr. Earth Sci 151, 225-240.

- 22.S R Olsen, C V, F S Watanabe, L A Dean. (1954) Estimation of available phosphorus in soils by the extraction with sodium bicarbonate. , U.S. Dep. of Agric. Circ 939.

- 23.C J Bouyoucus. (1951) A recalibration of the hydrometer method for making mechanical analysis of soils. , Soil Sci. J 59, 434-438.

- 24.Tushemereirwe W, Kangire A, Smith J, Ssekiwoko F, Nakyanzi M et al. (2003) An outbreak of bacterial wilt on banana in. , Uganda, InfoMusa 12(2), 6-8.

- 25.K D Broders, M W Wallhead, G D Austin, P E Lipps, P A et al. (2009) Association of soil chemical and physical properties with Pythium species diversity, community composition, and disease incidence. , Phytopathology 99.

- 26.S L Gebre, Ashenafi W, Kefelegn G, Alemayehu R, T M Manuel. (2021) Determinants of the spatial distribution of enset (Ensete ventricosum Welw. Cheesman) wilt disease: Evidence from Yem special district. , Southern Ethiopia, Cogent Food & Agriculture 7(1).

- 27.Atim M, Beed F, Tusiime G, Tripathi L, P Van Asten. (2013) High potassium, calcium, and nitrogen application reduce susceptibility to banana Xanthomonas wilt caused by Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum. , Plant Disease 97, 123-130.

- 28.Abera S. Minch University. Arba Minch (2017) Survey of enset bacterial wilt distribution in Mareka woreda. M.Sc Thesis. Arba.

- 29.Fikre H, Gizachew W. (2007) Evaluation of enset clone meziya against enset bacterial wilt. , Afri. Crop Sci. Con. Proc 88, 890.

- 30.Gizachew W, Kidist B, Blomme G, Addis T, Mengesha T et al. (2008) Evaluation of enset clones against enset bacterial wilt. , African Crop Sc. J 16, 89-95.

- 31.Muzemil S, Alemayehu C, Bezuayehu T, J S David, Murray G et al. (2021) Evaluation of 20 enset (Ensete ventricosum) landraces for response to Xanthomonas vasicola pv. musacearum infection. , Eur. J. Plant Pathol 161, 821-836.

- 32.Thwaites R, S J Eden-Green, Black R. (2018) Diseases caused by bacteria and phytoplasmas. In:. , Jones 296-391.

- 33.Tsegaye A, P C Struik. Wageningen University (2002) Analysis of enset (Ensete ventricosum (Welw.) Cheesman) indigenous production methods and farm-based biodiversity in major enset-growing regions of southern Ethiopia. Experimental Agriculture 38(3). (in press). PhD Thesis